Basic Economics

I just happen to be reading Thomas Sowell's book, Basic Economics. It's the updated and expanded third edition. He's added new information and entire chapters since the second edition. There are also quizzes on each chapter at the end. I like the quizzes because if I were studying this the way I should be studying it, taking these quizzes would help me remember what I've read. Page numbers are given to help one find the answers to the questions. And it's not even like the questions are that difficult if you've read the book. The way Sowell explains things, a lot of this stuff is common sense.Maybe I'm weird, but I'm finding most of this book fascinating. It could be because I'm interested in the subject. Or maybe I enjoy learning new things. Perhaps it's because I like seeing self-defeating myths smashed with a healthy dose of rationality and intelligent thought. There are a lot of real life examples in the book demonstrating how and why some economic theories work and others don't. One reviewer on Amazon simplistically titled his review, Capitalism Good, Communism Bad. He then went on to trash the book. Some people don't like it when their cherished irrational beliefs can't handle the reality of life. Sowell does compare the success of Capitalism to the failures of Communism, but due to the general disdain among our elite opinion makers of Free Market Capitalism, I think Sowell was right to make these comparison as often as possible. Not that it will quiet the free market haters, but it does offer lessons to those who will read and listen honestly. And it shows why people who still believe in Socialism and Communism just don't get it.

Reading this book helped me appreciate two articles in the current issue of City Journal. The first one is Hearts of Darkness by Michael Knox Beran.

Paternalism was supposed to be finished. The belief that grown men and women are childlike creatures who can thrive in the world only if they submit to the guardianship of benevolent mandarins underlay more than a century’s worth of welfare-state social policy, beginning with Otto von Bismarck’s first Wohlfahrtsstaat experiments in nineteenth-century Germany. But paternalism’s centrally directed systems of subsidies failed to raise up submerged classes, and by the end of the twentieth century even many liberals, surveying the cultural wreckage left behind by the Great Society, had abandoned their faith in the welfare state.Using logic, reason, and the 60 year record of failure of other African poverty reduction programs that have consisted of throwing money at Africa, he shows why the people involved in the current scheme are either deluded or are self-serving liars.

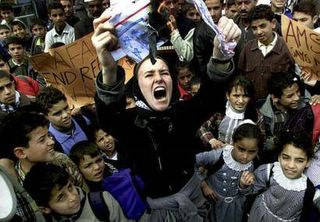

Yet in one area, foreign aid, the paternalist spirit is far from dead. A new generation of economists and activists is calling for a “big push” in Africa to expand programs that in practice institutionalize poverty rather than end it. The Africrats’ enthusiasm for the failed policies of the past threatens to turn a struggling continent into a permanent ghetto—and to block the progress of ideas that really can liberate Africa’s oppressed populations.

The intellectual cover for the new paternalism comes from economists like Columbia’s Jeffrey Sachs, who in his recent bestseller The End of Poverty argues that prosperous nations can dramatically reduce African poverty, if not eliminate it, by increasing their foreign-aid spending and expanding smaller assistance programs into much larger social welfare regimes. “The basic truth,” Sachs says, “is that for less than a percent of the income of the rich world”—0.7 percent of its GNP for the next 20 years—“nobody has to die of poverty on the planet.”

Sachs headed the United Nations’ Millennium Project, created in 2002 by Secretary-General Kofi Annan to figure out how to reverse poverty, hunger, and disease in poor countries. After three years of expensive lucubration, the project’s ten task forces concluded that prosperous nations can indeed defeat African poverty by 2025—if only they spend more money. “The world already has the technology and know-how to solve most of the problems faced in the poor countries,” a Millennium report asserted. “As of 2006, however, these solutions have still not been implemented at the needed scale.” Translation: the developed nations have been too stingy.

We’ve heard this before. The “response of the West to Africa’s tragedy has been constant throughout the years,” observes NYU economist William Easterly. From Walt Rostow and John F. Kennedy in 1960 to Sachs and Tony Blair today, the message, Easterly says, has been the same: “Give more aid.” Assistance to Africa, he notes, “did indeed rise steadily throughout this period (tripling as a percent of African GDP from the 1970s to the 1990s),” yet African growth “remained stuck at zero percent per capita.”

All told, the West has given some $568 billion in foreign aid to Africa over the last four decades, with little to show for it. Between 1990 and 2001, the number of people in sub-Saharan Africa below what the UN calls the “extreme poverty line”—that is, living on less than $1 a day—increased from 227 million to 313 million, while their inflation-adjusted average daily income actually fell, from 62 cents to 60. At the same time, nearly half the continent’s population—46 percent—languishes in what the UN defines as ordinary poverty.

Yet notwithstanding this record of failure, the prosperous nations’ heads of state have sanctioned Sachs’s plan to throw more money at Africa’s woes. In July 2005, G-8 leaders meeting in Gleneagles, Scotland, endorsed Sachs’s Millennium thesis and promised to double their annual foreign aid from $25 billion to $50 billion, with at least half the money earmarked for Africa. This increased spending, the Gleneagles principals proclaimed, will “lift tens of millions of people out of poverty every year.” No doubt, too, Africans will soon be extracting sunbeams from cucumbers.

The other article is, Criminalizing Capitalism by Nicole Gelinas.

Politicians and business pundits saw Enron’s collapse as an unprecedented market failure that cried out for a new remedy. Hadn’t the country’s best stock analysts believed the Enron “story”—permanently high growth through dazzling innovation? Hadn’t the nation’s bond-rating agencies awarded Enron a rating implying that prudent investors could lend to the doomed company? Hadn’t Enron’s “independent” auditors and outside counsel signed off on its crazy financial statements? And hadn’t Enron employees who had invested heavily in company stock seen their life savings evaporate?In its effort to clean up and micromanage the market, the government only makes things worse. As Sowell points out repeatedly in his book, controlling the market is an impossibility. Others have tried and failed. We have examples of these failures both throughout history and in today's world. But for some reason, people still think the market can be reigned in and made to behave, that it can be forced to be kind and gentle to "the people."

Yet Enron was actually an example of how markets work—messily, sometimes tardily, but in the end with ruthless efficiency. Even as most Wall Street analysts bought Enron’s sales pitch and accepted its financial statements, investors slashed the value of the company’s shares in half—far surpassing declines in the broader market—during the year before the accounting scandal broke. Investors had begun to withhold money before the government launched investigations. When Enron declared bankruptcy in December 2001, the regulators were left only to certify the market’s verdict. Those investors and lenders who hadn’t scrutinized the company lost money, as they should have.

Though Enron didn’t signal a market failure, it was a business failure, of course. The company overvalued its assets while undervaluing its liabilities—the oldest trick in the fraud book but also sometimes an honest mistake. In the 1930s, Samuel Insull, a utility entrepreneur who created the modern power grid, did the same thing; so did savings and loan banks in the 1980s. Enron’s chief financial officer, Andy Fastow, did it by vastly overstating the company’s assets and hiding liabilities, such as off-the-books sums owed to outside “investment partnerships” (he stole cash on the side, too). It was easy for Enron to perform accounting hocus-pocus because many of its assets, such as a one-of-a-kind power plant in India and speculative broadband ventures, were difficult to value. Enron’s assets were worth what Enron said they were—until the market decided otherwise. By booking future profits right away, Enron worsened its predicament; a mistake or a lie compounded over 20 years is far greater than one that covers only one year. What’s more, the company didn’t disclose clearly enough, in hindsight, that it was funding those precarious investment partnerships with its own stock—which it might have to replace with cash if the stock price fell.

Sowell's book, these articles, and reality all show that it can't.

All of this should be read in their entirety. In fact, I'm thinking about buying extra copies of Basic Economics for some family members.

Labels: books, City Journal, economics, Thomas Sowell

CHALLAH AKBAR

CHALLAH AKBAR

5 Comments:

Would you think 'Basic Economics" would be appropriate for a H.S. level course?

I'm not sure how or what they teach in H.S. econ, but I think this is appropriate for high schoolers. I think they would get all of the basics and a much better understanding of economic concepts. There are no graphs or charts, and no math is expected. It's an explanation but a darn good one. And the questions at the end of the book help to reinforce the important points of each chapter.

Harry,

I am not sure if you know about my blog at Double Nickel, but I gave you an award there!

Jennifer

penofjen.blogspot.com

(have I told you that I love Thomas Sowell!)

ma kettle,

Thanks for the award. I appreciate it, but would you be upset if I didn't pass it on? I don't want to insult anyone, and I read a lot of blogs that deserve this more than I do, but with the limited time that I do have for blogging (if you've noticed the long periods between posts) I don't have time to write a post that something like this deserves. I really do appreciate it though.

Harry

Of course you do not have to pass it on. I selected you because you truly blog with a purpose. I believe that you do deserve this, and am not worried if it stops with you.

I just wanted to let you know that even though you don't post often you do head on post. Thank you for keeping me informed.

Have a great day!

Jennifer

penofjen**:)

Post a Comment

<< Home